21 Flags

Every nation has its own mythology, a legendary history of its founders meant to unite and inspire those who follow. King Gilgamesh of Ancient Sumer, Romulus and Remus of Rome, and King Arthur’s defense of Britain with his mighty Excalibur are but a few of the numerous examples. Without a doubt, George Washington is the key figure in the lore of the United States, and among the most iconic images of the brave general is Emanuel Leutze’s George Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), painted 75 years after the fateful event. While historians debate on the accuracy of the details—would the Old Fox really be standing?—there is one fact most agree upon: that particular flag would not have been there. It was the Great Union flag, and not the familiar Star-Spangled Banner that would have accompanied old George on that fateful night.

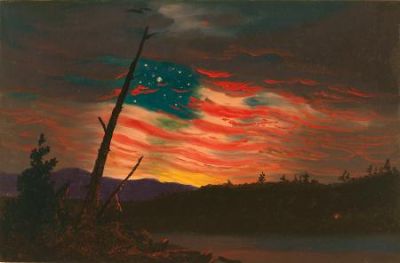

The United States flag has a mythology of its own, often celebrated in paintings that document turning points in the nation’s history. Leutze fully understood the patriotic appeal of the flag while toiling away on German soil to create his icon of Americana. This tradition continued in the able hands of Alfred Jacob Miller with his Bombardment of Fort McHenry (1828-30), a visual narrative to Francis Scott Key’s famous musical ode to The Star Spangled Banner, while Frederick Church later paid homage with his painting Our Banner in the Sky (1861), an allegoric sunset transformed into the famous tattered flag of Fort Sumter, where the Civil War ignited into full-scale war. More recently, the stars and stripes have become a means to critique and embody social and political unrest. In 1990, African-American artist David Hammons recast the familiar red, white and blue in the cloak of Marcus Garvey’s pan-African flag of red, black and green to highlight issues of identity and race in America with his African-American Flag. A few years later, Swiss-American Hans Burkhardt’s final painting, The Extra Stripe (1994), formed the flag from weathered burlap, replacing the field of stars with horizontal cruciforms, alluding to the casualties of war in protest of the U.S. involvement in the Middle East.

R. Nelson Parrish draws on this deep-rooted legacy in his exploration of the symbolism of the United States flag. His series of paintings, titled 21 Flags, is clearly based on the familiar pattern of stars and stripes, but abstracted nearly beyond recognition. By doing so, he compels the viewer to grapple with the scrapes, gaps and scratches while mentally reconstructing the familiar image hung vertically. The end result is neither a patriotic ode nor didactic lecture, but a process-driven technique that collectively speaks of the polysemic nature of the flag itself.

The series is a departure for the Alaskan-born artist, who is best known for his sculptural pieces, through which he deconstructs the opposition between man-made and the natural world. The works, which the artist terms “totems,” are fashioned from planed wooden planks wrapped in layers of transparent and color-infused bio-resin. The result is an upending of expectations: the natural objects become man-made geometric structures, while the languid flow of pigment is a result of natural forces. These works evoke the Finish/Fetish preoccupations of his West Coast forebears with a nod to Flow painting: John McCracken meets Peter Alexander meets Gerard Richter. The interaction of light with pigments suspended in the bio-resin slowly ebb and flow around the heart pillar of the individual works contrasted with hand-painted racing stripes, providing another layer of contrast to the mix.

At the core of Parrish’s process is a love of experimentation. Never satisfied, the artist continually pushes his materials to the point of collapse, ironically creating his own set of problems to be solved. After breaking down the processes he had painstakingly developed over many years, Parrish began to experiment with the individual components of his work as isolated motifs. The stripes became a focal point. Removed from the luminosity of the transparent resin base, he explored color and technique, spraying thin layers of paint on paper before scoring a series of stripes across surface, revealing the triage of colors hidden beneath.

In strictly formal terms, Parrish’s 21 Flags are descendants of these painterly investigations. The artist recalls a moment of hesitation as he pushed the abstract patterns into a more familiar iconography. He challenged himself to the task, and sent an image of this abstracted national symbol to a trusted friend who advised: pursue this path only “if you’re making a statement.” After a sleepless night, he rose with a sense of renewed urgency: he needed to create more flags. Through this initial urge came a new motivation: to use the symbol of the flag as a vehicle to consider what exactly it means to “be American.”

From this initial moment of creation, Parrish began to question: what does the flag symbolize? For whom? He revisited his past, from his youth in the Alaskan Frontier—both part of America yet separate from the lower 48, to his life as a working artist in Southern California, his experiences as a husband and more recently, as a father. During this process, Parrish excavated old black-and-white photographs taken years earlier, inspired by the likes of Robert Frank and William Eggleston, as he journeyed across the American landscape. The photos are exploratory images, ranging from somber to mischievous to hauntingly nostalgic, documenting the diversity of American life and livelihood. Looking back, these photographs signify the starting point for the artist’s current body of work.

On the surface, it might seem appropriate to relate Parrish’s 21 Flags with the iconic images of the United States flags by Jasper Johns in the mid-20th century, paintings that have acquired a lore of their own. Johns, initially inspired by a dream, painted his first flag in 1955 and continued to explore the symbol as a subject for several decades. These works represent the artist’s rejection of the existential angst Abstract Expressionism, the first internationally recognized movement that put American painting on the world stage. Instead, in the early years of the Cold War, Johns employs an emotionally charged symbol to embark on a perceptual game: is it a flag or a painting? With a nod to this legacy—naming the second flag in the series Jasper—Parrish also flips the equation. Where Johns used the flag to talk about painting, Parrish uses painting to speak about America.

Although each of the 21 Flags are clearly identifiable as derived from the American standard, the intention of appropriation is left purposefully vague. The flags are not meant to conjure a specific event, but a broader view of the past and present. Once begun, the cumulative layers of spray paint have only minutes before the paint is set. Every mark made upon the surface leaves its own history. The scrapes and scars act not solely as interruptions of the national symbol; they are a source of aesthetic beauty. The jagged stripes and striations of color evoke the frequencies of radio waves, cell phone signals, and—by abstraction—the distortions of news and communication through social media. The hollows and gaps provide visual relief; yet speak to breaks in history, to moments of silence and censor. These variations will inherently provide room for differing interpretations, as Parrish pushes the familiar construction of the flag to the point of failure.

For Parrish, these works are at once communal and deeply personal. The images are probing, critical and yes, patriotic. Each of the 21 Flags is unique, ranging from tricolor pageantry to variegated exhilaration to monochromatic solemnity, but they are united as a whole. The flags present a dichotomy, the technique produces a rugged aesthetic, but as works on paper, they are delicate. This allusion to the complexity and fragility of democracy is both overt and unapologetic. For the viewer, the paintings provide a focal point to meditate upon the diversity of meanings embodied by this familiar symbol. As we are bombarded with news of riots, protests, natural disasters and divided partisanship, the flags provide a moment of solace to ponder this question of what it means, or what it can mean, to be American.

Essay by MOLLY ENHOLM. Enholm is an art historian, freelance writer and artist based in Los Angeles. She is the former managing/digital editor of art ltd. magazine and contributor to several online and print publications, including Art and Cake, ArtScene, Fabrik, Hi-Fructose and Visual Art Source. In addition to writing, Molly also teaches courses on Modern, Contemporary and Asian art history at California State University Northridge.

Image footnotes:

1: Washington Crossing the Delaware. Emaneul Leutze, 1851.

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Muesum of Art.

2: Our Banner in the Sky. Frederic Edwin Church, 1861.

Image courtesy of Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

3: African-American Flag. David Hammons, 1990.

Image courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art.

4: Got to Go North. R. Nelson Parrish, 2017.

Image courtesy of Boat Yard Studios.

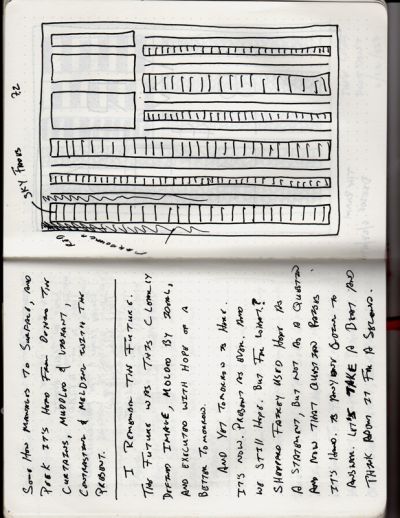

5: Scan from sketchbook.

Image courtesy of the artist.

6: Sly. R. Nelson Parrish, 2001.

Image courtesy of the artist.

7: Studio/process image. 2017.

Courtesy of the artist.

Colorfast

Catalog Essay: by David Pagel

You don’t need to talk to R. Nelson Parrish for very long to discover that he loves two things in life: barreling down mountainsides at breakneck speeds and making paintings that capture those magical moments when our perceptions of the world are especially vivid—so intense, stunning, and powerful that the rest of life does not pale in comparison so much as it seems to be a point of entry into mind- blowing highlights that make it all matter.

Love must be mentioned at the start because it distinguishes Parrish’s art from much of what’s out there, particularly in terms of what makes the headlines or appears in magazines. Snarky cynicism and know-it-all condescension play a large part of what passes for contemporary discourse, both in the art world and the world at large, where public discussions seem to be increasingly driven by anger, disdain, even hatred. In contrast, Parrish’s deliciously physical abstractions start with positive passions. Rather pointing fingers or acting out in a reactionary fashion, they take it upon themselves to seek out excitement and satisfy the human desire for experiences that are better and more thrilling than anything we had expected or anticipated.

The unknown is integral to Parrish, who goes out of his way to get out of his comfort zone, all the better to live life with the intensity it was meant for. His love of the unknown is anything but cuddly or warm and fuzzy. In “Color/Fast,” it’s ferocious. With purpose and passion, Parrish’s exhibition brings art and athleticism into graceful contact. That is rare and inspiring. It’s also a mark of Parrish’s originality. And it embodies his eagerness to share what he loves with others, despite society’s tendency to treat art and sports as if they had nothing in common.

In the popular imagination, artists have been thought of in all sorts of ways: as charlatans and schemers, sages and visionaries, romantics and rebels, misfits #77 (Untitled) 36” x 7.5” x 2.75” Color, Wood, Fiberglass, and Bio-Resin 2012 #81 (Untitled) 20” x 20” x 2.5” Color, Wood, Fiberglass, and Bio-Resin 2012 #93 (Untitled) 20” x 20” x 2.5” Color, Wood, Fiberglass, and Bio-Resin 2012 and dreamers. Sometimes their studios have been compared to research labs, where experiments are carried out and discoveries made. At others, the results of their labors have been compared to musical compositions, the wordless beauty of both evoking infinite emotions. Like doctors, artists have been called on to heal society’s ills. Like entertainers, they have been expected to amuse us. And since Pop Art brought the mechanics of the marketplace into the studio, artists have needed to be good at business, which, in this country, is often treated as the highest art of all.

Despite the range of roles artists have been called on to fill and the many purposes art has been called on to serve, it has rarely been paired with athleticism, either as a point of comparison or an endeavor with similar goals, perceptions, experiences, and pleasures. Parrish joins art and sports explicitly and implicitly, literally aligning elements of downhill skiing and abstract painting to profoundly affect our understanding of the various ways intense, bodily experiences alter our consciousness of the present and then, slowly and steadily, ripple through our memories long after those fleeting moments have passed.

“Color/Fast” consists of two bodies of work. The first is made up of Parrish’s trademark paintings: large-, medium-, and intimately scaled rectangles of variously tinted pigments suspended in various layers of glossy and foggy resin. Some of these works— which rest on the floor, are mounted on the wall, or hang from the ceiling—are boldly emblazoned with racing stripes, both vertical and horizontal. While Parrish’s meticulously crafted slabs of carefully balanced colors sit perfectly still, your eyes race across their sleek, shimmering surfaces and fly off into the vast spaces suggested by the depths that have been built into their patiently laid-up sections of poured and polished resin. Rather than functioning as decorative elements, Parrish’s racing stripes are physical emblems of your eyes’ activities: concrete graphics that hint at what happens when a viewer engages these highly energized—and rigorously disciplined—abstractions.

The second body of work consists of digital videos made by athletes Parrish commissioned to shoot runs down nearly vertical slopes in Alaska and across the horizontal surfaces of lakes in Utah. Unlike documentary films, these videos do not tell Video still: Bryon Friedman Heli Skiing in Haines, AK Contour Camera Perspective: Ski Tail Video still: TJ Lanning Inland Surfing on Jordanelle Lake, UT Contour Camera Perspective: Surfboard Nose stories about particular trips or adventures. Instead, they transform the sensation of speed—of the world whooshing by in a blur—into exquisite details that generate sharp perceptions, in the here and now. To do that, Parrish has turned away from helmet- mounted cameras, which tend to show viewers what the run was like for the skier, long after he has made it home safely and downloaded the data. With flatfooted directness, Parrish’s videos invite viewers to see the world from the point of view of a ski. Made with tiny cameras mounted on the front and back ends of skis, his videos are up-close and immediate, sometimes abstract and always moving. Showing particles of snow, flashes of sunlight, and splashes of frothy water, they highlight our capacity to perceive time and space differently: as both a speedy blur and a point of crystalline stillness. It’s a kind of high-keyed serenity or hyper-stimulated tranquility. Athletes often refer to such experiences as being “in the zone.” When that happens, the self is not lost so much as it merges with its surroundings and becomes part of a continuum that is vaster and grander than any individual. At once humbling and thrilling, it takes us away from ourselves only to take us more deeply into ourselves.

Similar experiences unfold before Parrish’s paintings. Each contains worlds within worlds, expansive universes that are different each time you enter them. Ranging from the microscopic to the cosmic, Parrish’s paintings invite us to focus on the big picture and to contemplate our place within it. Think of his works not as static objects to be tastefully displayed and casually enjoyed, but as tools: specially designed implements that get the job done, making more experiences possible by bringing more people face- to-face with the real thing. Like the skis Parrish needs to race downhill, his paintings take viewers on trips through our imaginations and beyond, into worlds that are a whole lot wider—and wilder—than the one we leave behind when we get into their zone.

David Pagel is a regular contributor to the Los Angeles Times and has written nearly 500 articles since 1997. He serves as Chair of the Art Department at Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California. Pagel is an art critic, educator, curator and bike enthusist.

Main&Sky

/ INTRO

Southern California-based R. Nelson Parrish was inspired by his native Alaska’s totem pole, which is typically a decorative narrative of the legends of a culture told through man’s relationship with the land. Since hunting, fishing, farming and trade traditionally were cornerstones of society, the totem pole united the stories of a community with its environment, through a form that inextricably linked art with nature. Requiring enormous labor, skill and craft, totems traditionally were made of wood, but today are also made of stone, glass and many other unconventional materials.

Parrish’s sculptural pieces are handcrafted of wood, aerospace aluminum and layered bio-resin, infused with splashes of vibrant color and racing stripes. The narratives depicted in Parrish’s work are conceptual and aesthetic tributes to seminal moments of expression or intense feeling, often triggered by nature and sports. Parrish seizes on the essence of the moment, and portrays its emotional story.

“With purpose and passion Parrish…brings art and athleticism into graceful contact.That is rare and inspiring. It is also the mark of Parrish’s originality.”

– David Pagel, Art Critic and Contributor to the LA Times

/ STORY

When moving at great speed across the landscape, the human eye can take in flashes of color and blurs of abstract shapes, and yet, at the very same time, it can also grab onto a single needle on a pine bough with razor clarity. In this sense, to both the artist and the athlete, one moment can feel like eternity, and all of eternity seems contained within that singular, but layered moment.

Through thick, hand-casted bio-resin and intense bands of pigment, Parrish’s totems juxtaposes two forms of speed—that of an athlete up against the challenging and euphoric elements of nature, and that of a human up against the rapid pace of contemporary society. The viewer is pulled into a catalytic nexus point where a moment of speed and blur passes into pause and lucidity—so that pure adrenaline crystallizes into presence and appreciation.

This work challenges the audience to examine their own experience of the tumultuous modern landscape and to navigate the world with the precision and inner authority of an athlete; thus, Parrish provokes within us a need for personal reconciliation between the forces of the fast and the slow, the static and the vibrant, the synthetic and the natural.

/ The Art of Endurance

From demanding physical feats to silent meditation, activities that push our bodies and minds to their limits are good for more than just a momentary rush.

Most of us thrive when we’re nesting in our physical and mental comfort zones: a state of being where we feel safe and secure and have the general rhythm of our lives figured out. Anything that takes us out of this bubble becomes unsettling and uncomfortable, and we’re generally apprehensive about—or do our best to avoid—situations that force us to face the great unknown. But the danger of subscribing to this philosophy of self-preservation is complacency—of becoming content with easy living instead of challenging our limits and tapping our full potential.

Pushing ourselves past our established habits can positively affect how we live our lives. One of the ways we can induce this effect is by engaging in endurance activities that thrust us far beyond our normal routines. These physical and emotional feats put our perceived limits to the test and can radically expand our capabilities and senses of what we can truly handle.

Endurance exercises have long been practiced across various religions, cultures and disciplines. For example, the Buddhist “marathon monks” of Japan participate in a seven-year training period called Kaihōgyō that involves walking more than 38,000 kilometers (23,600 miles) while engaging in intense meditation rituals. During a particular 100-day stretch in the final year of their quest, they cover 84 kilometers (52.5 miles) a day, which is twice the distance of a marathon. On the opposite end of the cultural spectrum, renowned artist Marina Abramovic is well known for pushing the limits of human patience. In her performance piece The Artist is Present, Abramovic sat in a chair during the opening hours of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and invited gallery-goers to sit opposite her for as long as possible. To take it one step further, she also maintained an almost-silent vigil for the three-month period of the piece. Of the 1,545 people who participated—including Björk and Lou Reed—many were reduced to tears. One man sat with her 21 times, at one point for seven hours.

Misogi is another endurance activity that has its roots in ancient Japanese religion. According to Christopher Kavanagh, an East Asian religion specialist completing his PhD in Cognitive Anthropology at Oxford University, most sources trace this practice back to a legend relayed in The Kojiki (a sacred Shinto text with records dating all the way from the early eight century). The legend describes how the deity Izanagi purified himself in a river after trying to save his wife from the underworld. “The core components of misogi rituals haven’t really evolved too much, but they’re constantly being adapted to fit the needs of different regional and social contexts,” Kavanagh says. Modern misogi rituals in Japan now include immersion in ice-cold water for extended periods of time, often with a meditation or fasting component added to the practice.

Enthusiasts outside of Japan have also drawn inspiration from misogi’s central tenets and have applied their own spin to them. Two notable misogi practitioners are Dr. Marcus Elliott, a Harvard-trained physician who has worked with some of the world’s top athletes, and the fine artist R. Nelson Parrish. The pair has even completed several misogi challenges together: In one, they crossed the 27-mile- long Santa Barbara Channel on stand up paddleboards with professional basketball player Kyle Korver, and in another they teamed up with three friends to run a combined six miles underwater holding an 85-pound rock, taking brief breaks to surface for air. The latter trial lasted a grueling five hours.

Elliott explains that while their version of misogi is rooted in the Shinto tradition, it is “a psychological and spiritual challenge masquerading as a physical one.” Despite the physically demanding nature of the quests they undertake, both Elliott and Parrish stress that misogi isn’t designed to be an “adrenaline junkie punish fest” or a way to check off certain challenges from a bucket list. Instead, misogi functions as a tool to initiate self-reflection and dismantle perceived physical and psychological barriers. “Pushing through pain has little to do with the goals of a misogi task,” Parrish says. “Misogi is about reflection and constantly striving. It’s about finding the rough edges around your comfort zone, smoothing them out, expanding and then finding the next edge.”

Both Elliott and Parrish see misogi as a continual practice that has grown into an integral aspect of their lives: Parrish likes to take part in a misogi event every six months or so, as he finds himself slipping into complacency a few months after completing a task. “The misogi philosophy is really something that should be practiced daily and can be as simple as holding your breath for three minutes,” Parrish says. “The big adventures are just the showcase events. The core of misogi is about challenging yourself out of your comfort zone on a daily basis.”

Endurance activities are incredibly arduous and take a toll on the body, but the psychological benefits they yield are equally as enormous. “We can talk about the chemical intermediates and hormones that are evoked in repetitive endurance exercises, but the truth is that there’s an insight—oftentimes spiritual and enlightening—that comes from these endeavors,” Elliott says. The effects of the sheer mental toughness required to complete these acts linger long after the last flight of stairs is scaled or that last bit of breath is exhaled: They translate into tangible real-life benefits, such as developing a thicker skin, broadening our perspective and giving us a stronger sense of self.

It’s easy for us to get too comfortable in the routines we’ve carved out for ourselves, but there’s immense value in prioritizing our self-improvement and challenging our minds and bodies to look beyond our perceived limits. By pushing our physical and mental faculties to the extreme, we can break through to a new level of what’s possible. So the next time life knocks us off-kilter, we’ll be able to right ourselves twice as quickly.

words by:

RACHEL EVA LIM

reprinted from:

Kinfolk, volume 19, 2016.